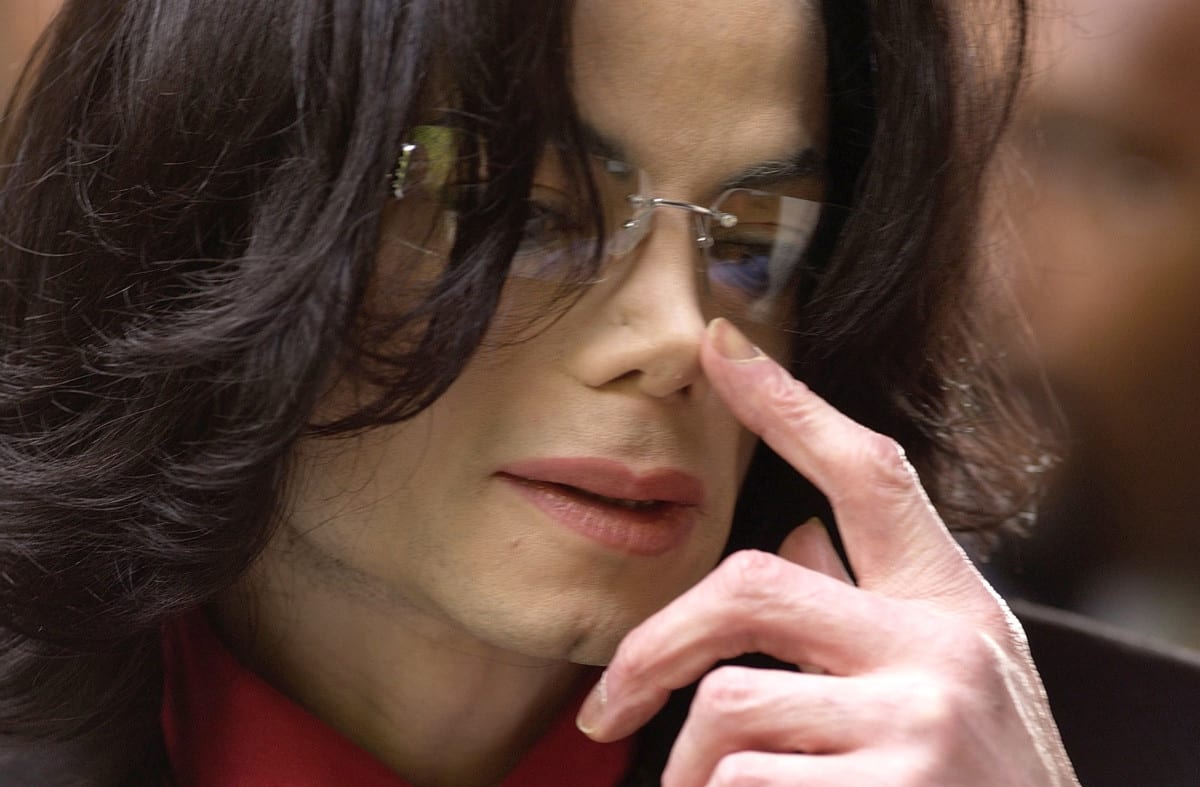

When popular Michael Jackson die, the public goes through a now all-too-familiar process: We mourn the loss on social media. We consume their work, downloading music, re-watching old movies, and scouring YouTube for old interview clips. And if the passing occurs unexpectedly, taking away a revered figure too soon, we seek answers to a single, nagging question: Why?

It’s been seven years since Michael Jackson died suddenly at the age of 50, and at least in basic terms, we know why. As established during the 2011 trial that convicted Jackson’s physician, Conrad Murray, of involuntary manslaughter, the superstar died because of a fatal cocktail of medications in his system, most notably an excessive amount of the surgical anesthetic propofol that Murray administered and that Jackson frequently used to help him sleep.

The Doctor, the Damage, and the Shocking Death of Michael Jackson” confirms all this in great detail, delving even more deeply into the events that occurred between the time Murray left a heavily drugged Jackson alone in his bedroom and the moment Jackson arrived on a gurney at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, where he would be pronounced dead a short time later. But the book’s scope also extends beyond the events of June 25, 2009, the date of Jackson’s death, to explore the many factors that conspired over the years to end the King of Pop’s life so prematurely.

Authors Matt Richards, a documentary filmmaker, and Mark Langthorne, a former music industry manager, have not written a book that boasts special access to Jackson insiders or mega-bombshell revelations about the Moonwalker’s confounding life. Instead, using testimony and evidence from Murray’s trial, as well as previously published media reports and books about Jackson, they have painstakingly connected the dots from the Gloved One’s reign in the 1980s to his final days as an addicted, cash-strapped artist attempting a comeback that he was neither physically nor mentally ready to mount. nikki-catsouras-death

“As far as Michael Jackson was concerned, 27 January 1984 was the beginning of the end,” Richards and Langthorne write, referring to the day Jackson suffered third-degree burns on his scalp while filming a Pepsi commercial. According to the book, initially published last year in Britain, the singer was in such pain that he took Percocet, Darvocet, and, during his subsequent scalp treatments, large amounts of Demerol, all of which kick-started decades of dependence on narcotics. That dependence, coupled with financial difficulties that would compel him to agree to a demanding string of performances in London in 2009, set the table for Jackson to become more reliant on Murray, a doctor facing his own money troubles.

“Dr. Conrad Murray was not, nor ever would have been, suited to be the caretaker of a complicated patient like Michael Jackson,” the authors state. “And from the moment they met, their fate was sealed.”

returns often to this idea that Jackson’s demise was inevitable, not only because of Murray’s negligence, but also because of previous doctors who accommodated Jackson’s desire for propofol and other drugs, and Jackson himself, who apparently considered himself immune to the risks. Even though followers of the Murray case and fans of Jackson may be aware of many of the details outlined in “83 Minutes,” revisiting all the pieces of the puzzle in a single volume has a powerful narrative effect.

Richards and Langthorne manage to be respectful of Jackson without shying away from the harsher truths about his life, but there are some moments when “83 Minutes” veers into invasive territory that isn’t always illuminating. A full two pages are devoted to a description of the messy interiors of the bedrooms Jackson inhabited when he died; considering that the morbidly curious can easily Google photos of the scene, which were released during the Jackson family’s 2013 wrongful-death trial against concert promoter AEG Live, all those paragraphs seem especially unnecessary.

goes so nitty-gritty on the details surrounding Jackson’s death that the book doesn’t have the room or inclination to fully address larger issues, such as the so-called VIP syndrome that enables the rich and extremely famous to receive special treatment, even when that treatment may not be in their best interest. The recent death of Prince — another iconic pop star who died with an excessive amount of medication in his system — is a reminder that Jackson’s death was neither the first nor the last preventable loss of extraordinary talent. Why does this happen to people whose art has meant so much to so many? That’s a question that, sadly, we never get to stop asking.